By JW McNay/managing editor

Century-old injustices revealed

A guest speaker presented what she called a lesser-known history of Texas-Mexico border relations 100 years ago and the parallels that can still be drawn from that time today.

Monica Munoz Martinez, Brown University American and ethnic studies assistant professor, spoke to students, faculty and community Oct. 17 on TR Campus about her book The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas.

Martinez is interested in the relationship between history, memory and power as well as how history is remembered.

“I think about what it is: The relationship between mainstream histories, the histories that we see in museums and that we see in public school lesson plans, and how that’s different from the histories that people who are members of racial and ethnic minorities learn at home,” she said.

From 1848 to 1928, mob violence against ethnic Mexicans has “largely been forgotten in public memory,” Martinez said, adding that “ethnic Mexican” refers to U.S. citizens racialized as Mexican and Mexican nationals living in the U.S. in this era. And racial violence against ethnic Mexicans in Texas at the hands of law enforcement also rose between 1910 and 1920, she said.

“This decade itself was a particularly brutal period when ethnic Mexicans were criminalized and harshly policed by an intersecting regime of vigilantes, state police, … local police and U.S. Army soldiers,” she said.

TR student Cindy Tovar gets her book signed by guest speaker Monica Munoz Martinez. Tovar was one of 20 attendees to receive a free copy.

Surviving families and friends of these victims were “unsettled with the injustices they were left with,” she said. A lack of due process in these times failed to get justice for victims of racial violence and their families.

“I’m committed to finding ways to research [and] recover these histories but also to make them public,” Martinez said.

She highlighted different cases in the presentation including a double murder of the grandfather and great-grandfather of Norma Longoria Rodriguez. Rodriguez learned about it as an adult and spent decades trying to document it, but there are no records of the deaths or an investigation, Martinez said. However, Rodriguez did have the land deeds for them as well as a teaching certificate for one who was also an elected official.

“That case of the double murder gives us access not only to the kinds of violence that wasn’t investigated but also is a reminder that some people who lost their life were pillars of the community,” Martinez said. “And if they could be murdered, it reminds us that class, citizenship and status was not something that protected ethnic Mexicans from violence in this era.”

In the post-speech Q&A, TR student and student government organization vice president Dakota Flores asked Martinez how students can help publicize this history and if more ethnic studies classes would help.

“I think the most important thing students can do is to learn themselves,” Martinez said. “And also ask for these kinds of classes to be offered back at their high schools where you came from and also at the universities that you’re at right now … and where you’re going to go to school because there should be a demand for these kinds of classes.”

Flores is biracial but doesn’t really feel connected with his Hispanic heritage. However, the presentation and its visuals affected him, he said.

“Sitting and listening to the stories and then looking of the faces of the people that are more connected to that just made me more emotional just thinking about it,” he said.

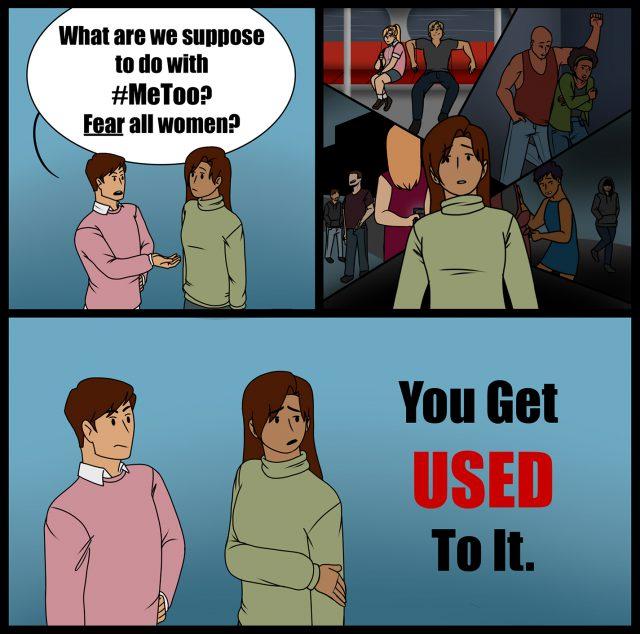

Martinez hopes making this history more public will also provide a reminder to the harms of criminalizing racial or ethnic groups and denying them due process.

“When people are looking around in their communities today for racial and ethnic minorities that are suffering from police brutality or racial profiling or for the anti-immigrant sentiment that they hear being espoused by politicians, that history really resonates with what happened 100 years,” Martinez said. “And we have to learn from history so that we don’t make the same mistakes today.”