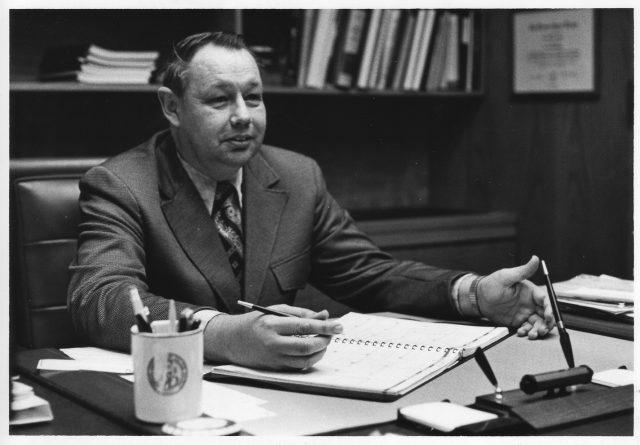

By Kathryn Kelman/editor-in-chief

Faculty, staff remember his TCC tenure

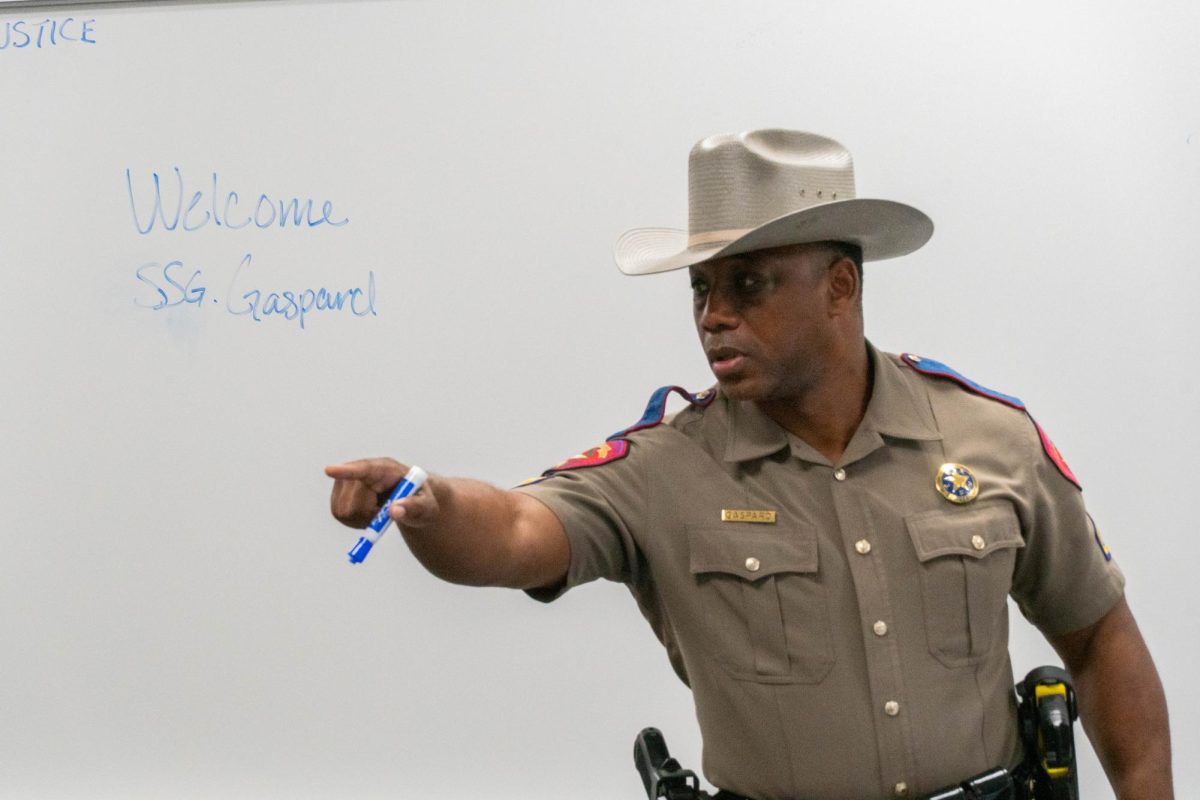

C.A. Roberson, TCC’s second chancellor and one of the college’s first employees, died Jan. 29 following complications from a short illness. He was 88.

Roberson was one of the three men who laid the foundation for what TCC has become today, said vice chancellor emeritus Bill Lace.

“The thing I remember best is that he had an eye on everything and everybody,” Lace said. “He cared so much.”

Roberson had a rough exterior, but he cared deeply about students, faculty and staff and always looked for ways to improve, Lace said.

Roberson succeeded founding chancellor Joe B. Rushing. He rose through the ranks at TCC from director of finance to administration vice president to executive vice chancellor and finally to chancellor. Roberson served TCC for 30 years, helping the college grow from its initial single-campus with an opening enrollment of 4,200 students to a college that today serves more than 50,000 students on six campuses.

One of Roberson’s responsibilities as finance director was to supervise construction of both South and NE campuses, built between 1966 and 1968. Despite having a director of maintenance, Roberson was on the sites all the time as they were being built, Lace said.

“He was really hands-on, and that was in addition to having to buy everything that went everywhere,” he said. “When you stop to think about building a campus, that’s everything from the buildings themselves to the light fixtures to a rack for a roll of toilet paper in the bathroom.”

Lace recalled a story he’d been told about Roberson from when South was being constructed. He noticed the campus cafeteria didn’t have a grill for hamburgers. It turned out the person who designed the cafeteria had no clue what a community college kitchen should be, he said.

“He was planning to serve salads and crepes and things, and C.A. said, ‘No, we want hamburgers,’” Lace said. “So they had to do a major revision of the kitchen at the South Campus, and I think probably the students were appreciative of that.”

Roberson was always careful about spending money, Lace said. If people on campus wanted funding for something, they needed to present him with a good case when they went to ask for it, Lace said.

That’s where his nickname came from: “The Abominable No Man.”

“But if it was important to the welfare of students and the welfare of faculty and staff — he did not hesitate to spend money,” Lace said.

Former associate professor and management program coordinator Mary Alice Smith said she admired how fiscally responsible Roberson was.

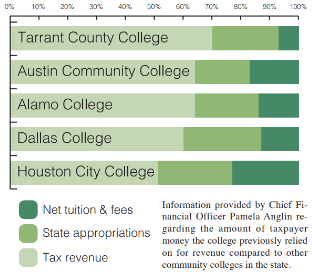

“I appreciated the fact that we were sometimes one of the few colleges in the state that were working in the black and not the red,” she said.

Roberson was a country boy with an utter brilliance in higher education finance, said former community relations director Don Newbury, who joined the district a few months after Roberson did.

The two became friends almost immediately after Newbury was hired.

“I’ve never known a person with a greater reach of understanding and patience and willingness to listen to everyone including students, maintenance people, janitorial, faculty and fellow administrators,” Newbury said.

In a 2015 interview with The Collegian to mark the college’s 50th anniversary, Roberson said his favorite moment was South Campus’ opening in 1967. Getting that campus opened and watching all the students flood in was the best feeling, he said.

“We bridged a gap there, gave students a chance to get work done,” Roberson said.

Newbury said a person didn’t have to work at TCC for a long time to realize the former chancellor was the “real deal.”

“He was present. He was persistent,” Newbury said.

Former student publications director Eddye Gallagher recalled how much Roberson cared for the students, faculty and staff.

“He knew everybody’s name,” she said. “It was unbelievable.”

Roberson went to department meetings and would even stop in people’s offices to chat for a while, she said.

“Rushing was really nice, but he wasn’t like that [Roberson] and we haven’t had a chancellor since then that was like that,” she said.

Coming to campuses and talking to people was a casual thing with Roberson, she said.

“He would just walk into your office and sit down and start chatting,” Gallagher said. “There was no pressure. It was like sitting down and having a cup of coffee.”

At Roberson’s funeral, Newbury quoted lyrics from “Lean on Me” because everyone leaned on Roberson, he said.

“He was leaned on by other colleges too, not just in Texas but all over the nation,” he said.

Roberson was a respected leader in higher education and community college finance. In fact, while he managed the business side of the college in its early day, he was also busy at the state level, serving as the point person for what was then Tarrant County Junior College with the Texas Legislature when it was in session, Lace said.

“He was very active in not only getting funding for TCJC but for all community colleges in Texas,” he said.

In 1966, Texas community colleges were responsible for getting their own funding, but Roberson worked with state leaders to institute a formula funding system that Lace said was a fairer, more equitable way of securing funds.

“He was really the expert in Texas and one of the most knowledgeable in the country on funding for community colleges,” Lace said.

From 1953 to 1993, Texas governors sought Roberson’s participation on various boards, commissions and committees.

“C.A. impacted hundreds of thousands of people in policy and in practice and in practical approaches,” Newbury said.

The two often engaged in friendly arguments that would end with Newbury telling Roberson that he didn’t report to him.

“He could have a serious countenance that could seem stern to some, but underneath was a puppy dog unquestionably,” he said. “He had a Neiman Marcus mind in a JCPenney suit.”

In 1996, Roberson was awarded the Honorary Doctor of Educational Leadership degree from the University of North Texas. He never had the time to get an “earned” doctorate, but when one thinks about it, anyone can get one of those, Newbury said.

“There’s a lot of truth in that because the honorary ones usually go to the very rich and/or the great servants,” Newbury said. “And he [Roberson] was the latter.”