The molestation of children is once again a major issue in the Catholic church.

Nearly 600 children still await reunification with their parents due to the Trump administrations “zero-tolerance” policy at the U.S.’ southern border.

Almost half of the world’s population, more than 3 billion people, live on less than $2.50 a day while another 1.3 billion live on less than $1.25 a day.

The life expectancy of trans women of color is 35.

The U.S. has had 235 mass shootings so far in 2018, according to the Gun Violence Archive at the time this editorial was written.

The list of issues plaguing the world today goes on and on, but what is there to do about the state of this world and where does one start with trying to fix it? What should be fixed first?

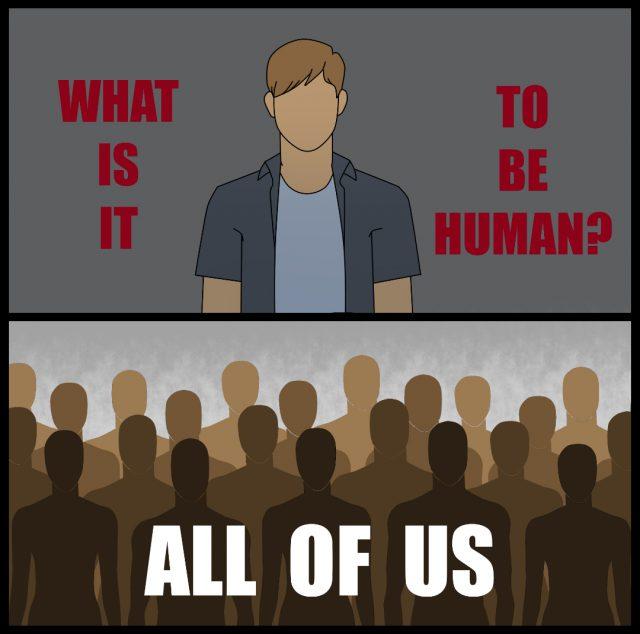

Unfortunately, there is no easy answer, but nearly all of the world’s problems do boil down to one question — What is it to be human?

Ai Weiwei put it wonderfully in his New York Times opinion piece Aug. 23.

“We can only define ourselves by continually re-evaluating our humanness,” he wrote.

Everyone can agree that this time period is quite distinctive. Different labels exist for it — the era of globalization, of technology, of information, of late capitalism, etc. — but all note the world’s new situation.

The new state of the world is due to the fact that humans are freer than ever before because of increased access to information, knowledge and assistive technology.

Times have indeed changed. And though millennials are often blamed, the real issue is that despite the new freedom, the forces that have historically constricted opportunity — states, religions, ethnicities, socioeconomic class, gender and more — are simultaneously dissolving and being reorganized. And while some are dying altogether, others are growing exponentially stronger.

The rapidness with which the world is changing can be mind-boggling and make it hard to stay grounded, compassionate and open-minded as people try to figure out where they belong now.

And this question, “What is it to be human?” changes as the world does. The answer from the ‘40s is different from the answer today as future answers will differ from today’s.

But it can’t be avoided.

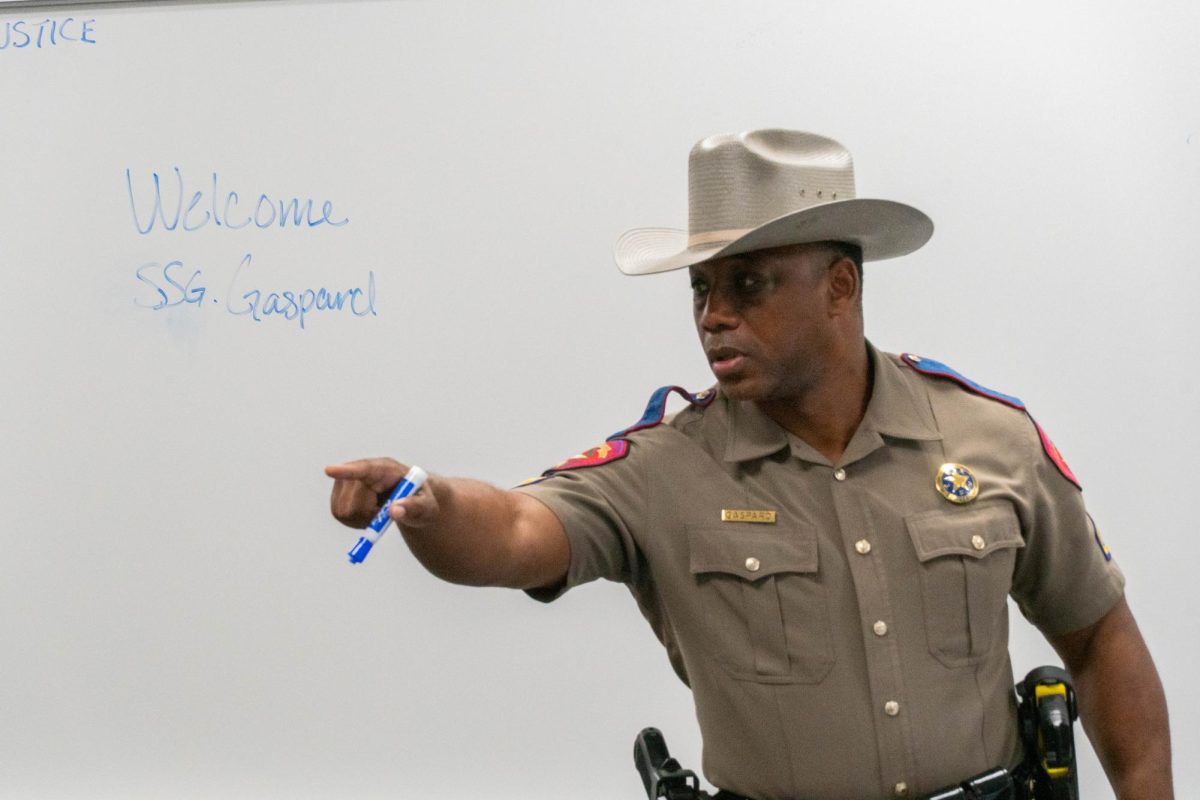

It must be asked, and it must be asked repeatedly. When it’s avoided, the political and cultural disagreements that lead to things like family separation, police brutality and global poverty and hunger crises arise or are perpetuated due to the reluctance to face this question head-on.

Humankind includes everyone, and it always will regardless of who is in power and what ideologies they use to rule. The world’s saving grace will always be how we treat one another and stand up for the vulnerable, the forgotten and the forsaken.

That’s why asking “What is it to be human?” and then answering it is so imperative. It is an individual’s and society’s moral compass.

Should we lose sight of our humanness, the injustices happening around the globe will at the very least continue if not grow and multiply.

But by determining who we are, who we want to be and how we want history to remember us during this time of immense change, we can begin to break down the laundry list of evils that plague us.