NE government instructor Derrick Shelton, a New Orleans native, still lives with the impact Hurricane Katrina left on his life.

Shelton was in Louisiana leading up to the tragedy and had to help his family evacuate the state before it was too late.

“Honestly, I’m still experiencing Katrina even though it’s been 20 years,” he said. “I still hurt. I still feel the pain. We lost everything.”

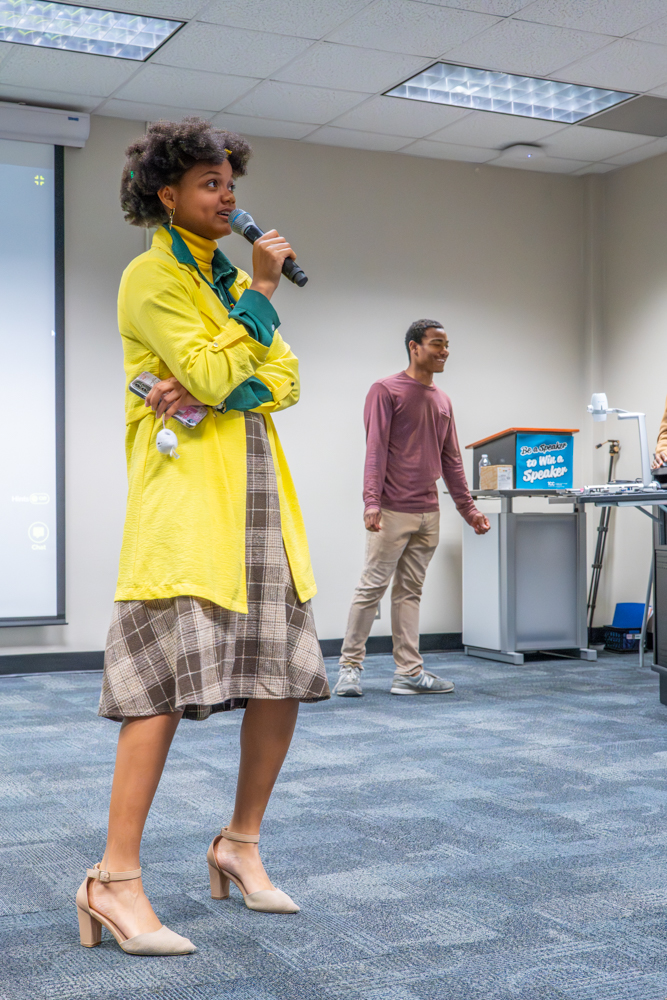

Shelton was part of a five-person panel spanning from instructors to counselors during an anniversary event on NE Campus Sept. 9, discussing the events that unfolded after the initial hit of the hurricane changed the trajectory of Louisiana’s landscape.

“The storm exposed deep vulnerabilities in disaster preparedness, infrastructure and social equality, prompting national reflection and reform,” NE history instructor Sara Reed said. “The Gulf Coast and particularly New Orleans would be forever changed.”

Like any seasoned Louisiana resident, Shelton was used to storms coming and going. He explained that a gut feeling told him Katrina was going to be like none other, and he followed it.

“As the storm passed, we started watching the news and then realized the levee had broke,” he said. “No one ever imagined that the levees would have failed, and that’s when that hit me. I couldn’t go home.”

Grant Griffin, a NE mathematics instructor, broke down the science behind the Louisiana levee systems during the panel.

Levees, as he explained it, were meant to protect the land from rising waters.

A combination stemming from New Orleans already sitting in poor soil sinking into a “bowl” shape, disorganized and inconsistent engineering in levee structure as well as inexperienced city board members meant failed flood prevention.

“Portions of the city are above sea level. The outside edges have been built up, and so it creates that bowl effect that we mentioned,” he said. “The problem there is, once water gets in, it’s extremely difficult to get it out.”

This pointed to one of the reasons Louisiana suffered as much as it had during the storm, but history instructor Adam Guerrero warned that plenty of misconceptions about the issues stemming from Katrina created a longstanding stigma.

Guerrero recalled reading the first news reports spreading information about looters, snipers and a general sense of lawlessness.

“When you listen to authority figures who were actually on the grounds – Gen. [Russel] Honore, for instance, who is the leading general in charge of the rescue mission – that didn’t happen,” he said.

What outsiders saw as malicious break-ins and advantageous theft, Guerrero said was more likely due to people trying to survive while aid was being delayed.

“I mean, I almost leave it to any individual,” he said. “What would you do? Would you starve to death or die of dehydration, or would you go get the necessary materials?”

Part of understanding how residents were affected by the events of Katrina meant knowing how specific communities were hurt. Angela Shindoll, a psychology instructor, shared the trauma effects on Louisiana residents.

Shindoll had family who were also affected by Katrina and recalls what the experience was like coming to them to help when the state was reopened for access in October.

“There’s just piles and piles and piles of piles of trash,” she said. “The smells are just unbelievable because you think about water that sits there, it hasn’t been pumped out yet.”

Classic PTSD symptoms like severe anxiety, depression and fear lasted long afterward, Shindoll explained, and shed light on the fact that specific communities like the upper Ninth Ward in New Orleans faced even more trials than other areas.

“Many minority populations, specifically those that were living in the high poverty areas in the Ninth Ward faced a lot already systemic barriers, and so they received even more delayed aid,” she said.

Shelton explained that evacuating with his family changed a lot about the direction of his family’s life, but he knew that coming to Texas meant he had no option but to succeed.

“My story is a story of resilience and luck and assistance from a lot of caring people in Texas,” he said. “The sudden moved to Texas had a dramatic impact on my identity, and I had to take care of my family, period.”