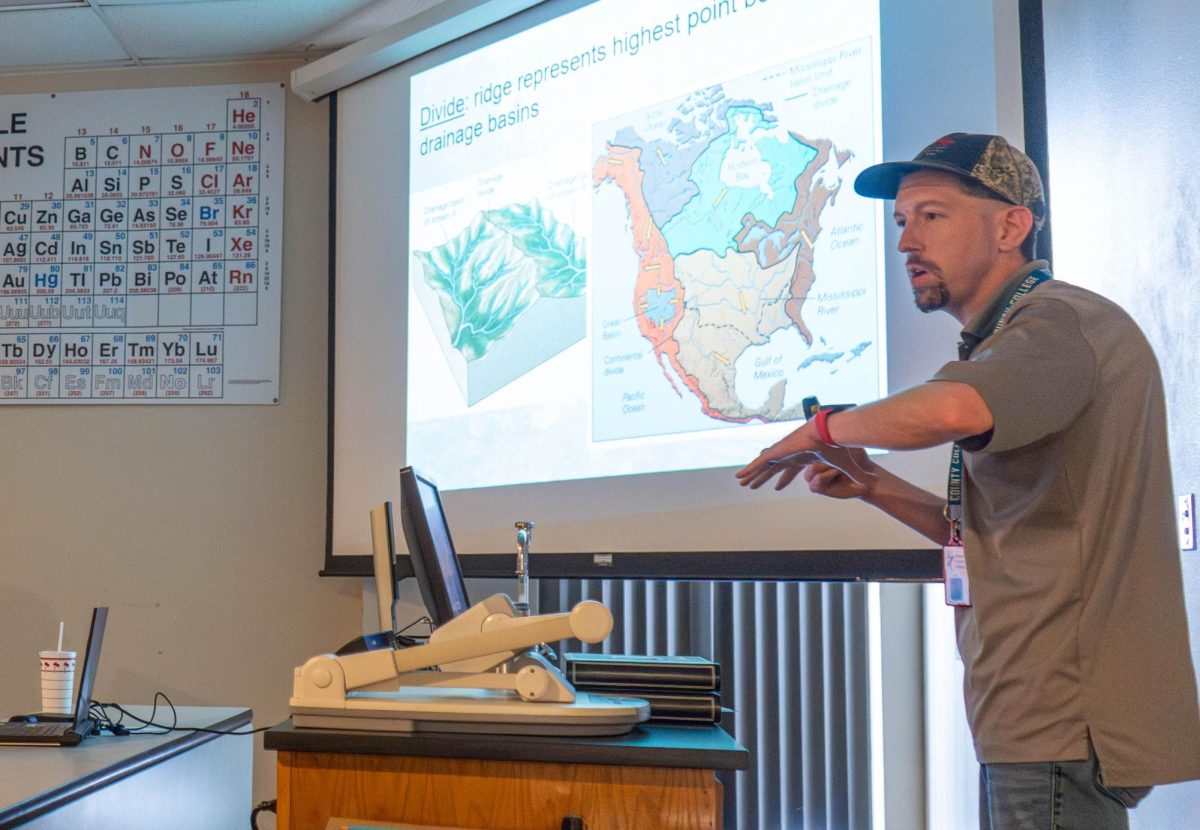

The sound of keys jangling and sandals flopping can be heard as the professor walks through the hallway with a smile on her face greeting everyone her eyes meet.

After entering the classroom, her shoes come off, and she stands at the podium with an Expo marker in hand ready to begin the lecture.

NE Campus government professor Lisa Uhlir teaches in an old-school way. No projectors. No online assignments. Just a whiteboard, some notes and her voice. And her students can’t seem to get enough.

Uhlir recalled being asked by a student what the secret to being a great professor was. She said, “to care.”

“If you don’t care, it doesn’t matter what you do. You’re not going to be good at it,” she said. “Teaching has given me that ability to care.”

From wanting to be a veterinarian, then a geneticist, then a spy for the CIA and then eventually landing on becoming a teacher, Uhlir has gone down many paths of life. Through it all learning has always been something that she prioritized.

“I love teaching. I love school,” she said. “If I could have just stayed in school as a student forever, I would have got like 80 degrees or whatever, but it’s not feasible.”

But learning wasn’t always easy for her, partially because of her Native American heritage.

The way Native people learn is drastically different than how children are taught in the public school system, she said. In Western education, they use math and the scientific method to find the answer, while Native learning, according to Uhlir, is rooted in observation and patience.

She explained that in order for a Westerner to figure out how a bird flies, they would take it apart, dissect it and measure the length and width of the bird.

“We learn through mostly observation over a long period of time,” she said. “Then we, overtime, go ‘OK. When it flies, what does it do? How does it do it? Where does it go?’ We watch the winds and then we come up with conclusions.”

This makes it difficult for Native children to adapt to Western schools. Uhlir, being half Native American, faced similar challenges.

Uhlir spent her early childhood in northern Michigan on the Ojibwe reservation, where her father is from. Later, her family moved to southern Michigan where she started pre-K in a Lutheran private school that closely followed her mother’s beliefs.

At the private school where they knew she was Native, she was described as a tough kid. Teachers would say “she talks too much,” or “she won’t sit still.” She constantly got bad grades and was pulled into teacher/parent meetings where the teachers would make remarks about Uhlir’s father and whether he would be in attendance because of the negative stereotypes that were associated with Native Americans.

When they moved to a new town, Uhlir’s mother decided when enrolling her to check the “white” box. Uhlir was then described as the perfect student with straight A’s. She was seen as helpful rather than talkative. This led Uhlir to deny her heritage for a while because it gave her benefits. It wasn’t until high school that she reconnected with her past and heritage.

Uhlir described the challenges of being a child split between two different ways of life between her mother and her father.

“Having both of them in one way has really helped me to see the world from many ways,” she said. “And helped me relate to students better in some things and understand.”

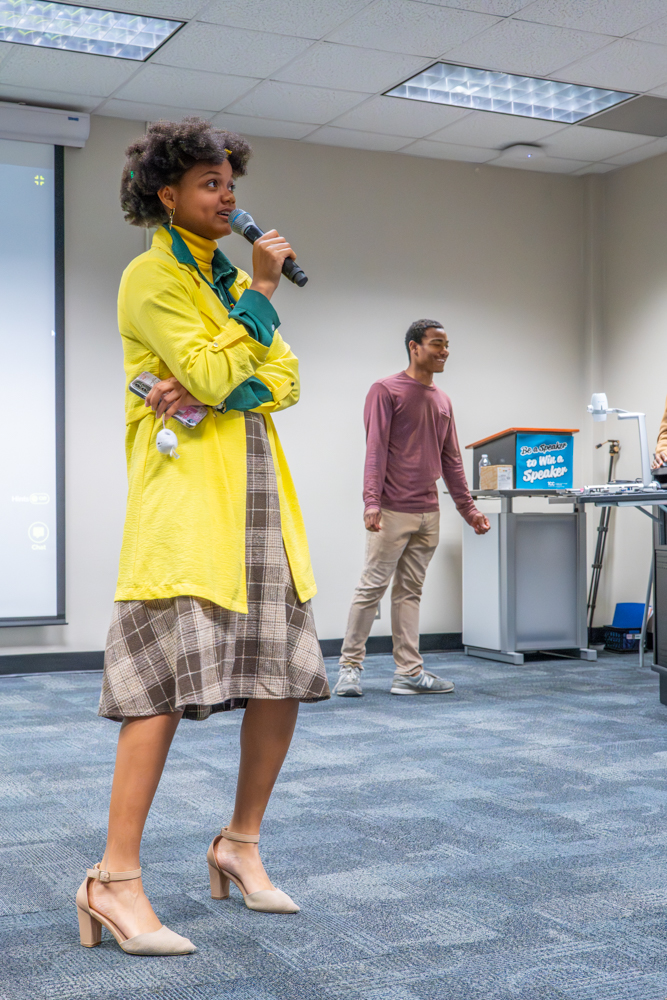

NE student Isaiah Anderson sees that firsthand. He said he enjoys her class because she goes in-depth into government topics, giving real-world scenarios that help him understand better.

“I’ve dropped a lot of classes in the past because teachers just didn’t teach the way I learned,” he said. “So, it’s refreshing and nice to be able to have a class that makes a lot of sense to me.”

Uhlir is always looking for ways to engage students in an era of technology and isolation.

“People just don’t interact the way we used to when I was younger,” she said. “So, people are very open to having somebody notice that they exist and talk to them and care about them.”

To increase direct interaction with her students, she has started a new type of office hours she calls “walking hours.” During this time, she walks around the school gym and allows students to join her and talk about anything from class questions to life issues.

“The cool thing about walking hours is it’s an informal environment, and it’s a group environment,” she said. “I think students will feel less intimidated to come up to me and to just kind of chat.”

Uhlir is a pool of knowledge. She has a bachelor’s degree in Russian studies, a master’s degree in international affairs with a minor in international organizations and administration and a doctorate in political science with areas in political theory, American government and international relations as well as a high honors in political theory.

She uses this knowledge to help those at TCC in any way she can.

Every Tuesday, Uhlir is one of the few mentors in an event titled “Mentors, Mindset, & Money: Intercultural Network & Mentors,” an event that helps students prepare for lifelong financial and civic impact.

NE student and regular attendee Amelia Ignatenko said having Uhlir as both a professor and mentor has helped her foster long-term skills in financial management and test-taking abilities.

“I used to have a lot of anxiety about taking tests,” she said. “Now, whenever I take a test, I’m much more cool-headed about it.”

Uhlir is often asked why she teaches at TCC when she has so many degrees and worldly knowledge. She said at first it was out of necessity. After finishing up her doctorate, she had just gotten divorced and become a single mom. Although she was offered jobs at universities like UTD and UTA, TCC was the only college willing to work with her schedule.

She then grew to prefer TCC because she felt she could connect with the students better.

“I think I make a bigger difference here,” she said. “I think I can make a bigger change and have a bigger impact here.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Because of Lisa Uhlir’s religious beliefs she can’t have her photo taken. “Because we believe in reincarnation, we don’t want to be tied to our past life,” she said. “Our personal belongings, a photograph of me, I’m attached to that, and you’re attached to that. So you’ll be crying, you miss me, etc., and my spirit won’t want to move on, because there’s longing and stuff left here.”