By Melissa Smith/reporter

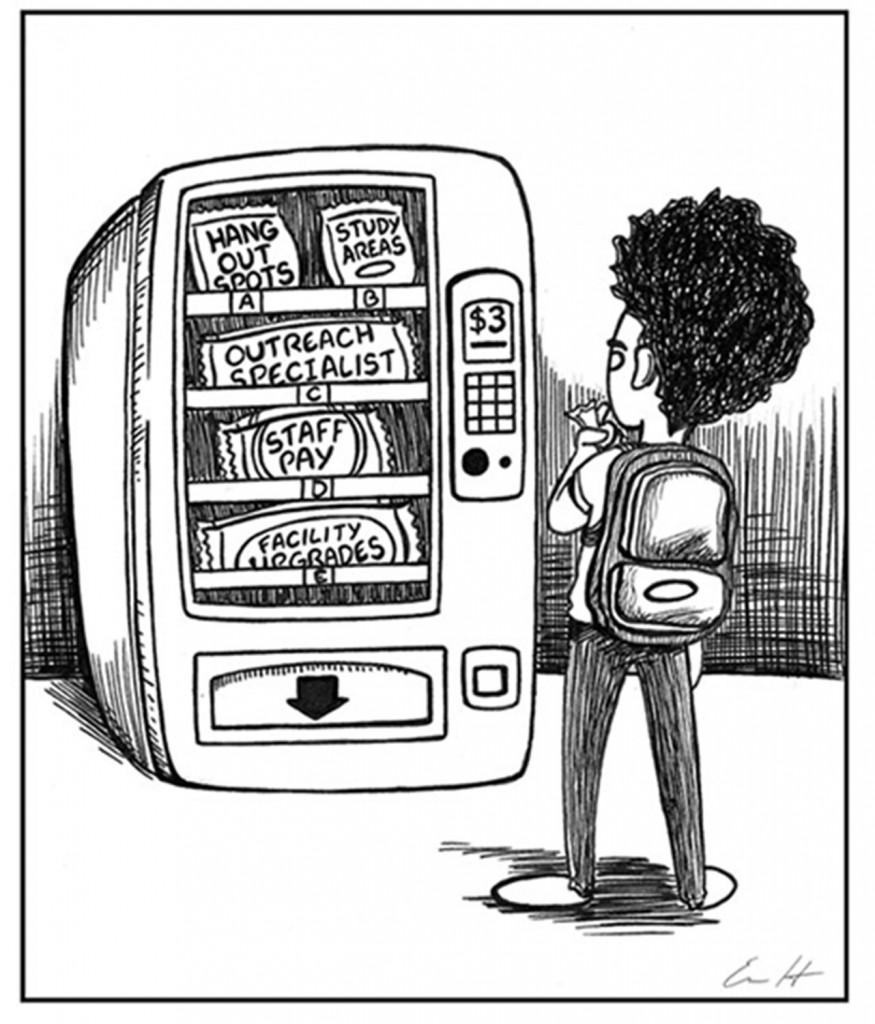

Illustration by David Reid/The Collegian

Before donning pajamas and kicking back for a trigonometry lecture delivered on the web, prospective students should carefully evaluate the differences between distance learning and on-campus instruction.

Arguably, the most appealing aspect of distance learning is that most courses require few or even no on-campus class meetings. In fact, the TCC Associate of Arts degree can be earned entirely through distance learning courses.

While students could theoretically earn their degree wearing pajamas, in reality, a student’s choice to opt for distance learning usually has little to do with wardrobe flexibility.

“I could have taken live instruction, but DL allows me to save time and money on commuting,” said Jerry Scripter, a TCC student who has earned nearly 20 hours of credit online.

Many students choose distance learning because work and/or family obligations make attending on-campus courses impossible. For some students, distance learning is the only way they can take college classes at all.

“I am excited to have the opportunity to take these courses online as I doubt I could work classroom attendance around my work and family responsibilities otherwise,” said Chris Bickerstaff, a TCC student who took distance learning courses for the first time this spring.

The flexibility of distance learning leads some people to believe that everything about distance learning is flexible — including course workloads. But this is rarely the case.

“We often get students who believe online classes are much easier because a student does not have to come to campus. Often, students are surprised at the amount of work that is required in an online course,” said distance learning director Kevin Eason.

The myth that online courses are somehow easier or require less work than the on-campus equivalent is something NE speech instructor Jamie Kerr is quick to dispel.

“You will do more work for the online class than students in my on-campus class will do,” she says during the mandatory on-campus orientation for her distance learning Fundamentals of Speech Communication class.

More often than not, the time commitment a student must make to be successful in a distance learning class can be linked to the student’s familiarity with and prior preparation for the academic subject itself.

“The programming classes have been all new material, and the time commitment is far greater than the other classes,” Scripter said.

The degree of difficulty in understanding and synthesizing a course’s learning objectives varies widely from student to student. What may be a grueling class for one student may be a breeze for another.

For example, Bickerstaff said he was “loving chemistry as an online course” and found the website where students completed much of their homework to be “amazing and instructive.” But his classmate, Casey Harris, didn’t share this sentiment.

Harris, who is seeking his second baccalaureate and says he has taken numerous distance learning courses, described the same class as “the worst experience.”

Regardless of how prepared they are, students who have difficulty mastering the technological aspect of distance learning will certainly need to commit more time to do well in an online class. Eason hopes TCC’s new distance learning management system, Blackboard, will make that a bit easier.

Blackboard is described by its creators as the “new generation of ducation,” and TCC’s distance learning site says Blackboard will serve as “both a portal and a learning management system [by providing] access to tools such as announcements, email, clubs and virtual classrooms.”

The students who gravitate to distance learning education are those who are comfortable with adopting new technology and who usually enjoy using technology in all facets of their lives, Eason said.

Pay special attention, masters of social media and wielders of smartphones: Blackboard has apps for Apple, Blackberry and Android products that allow students to complete coursework even when away from a computer.

But being tech-savvy isn’t the only factor that determines the success of a distance learning student. As with live instruction courses, the likelihood of success depends in large part upon the student.

“We get a wide range of students registering for DL courses, including many who do not even have the basic academic skills necessary for success, such as typing speed, technical knowledge and reading comprehension,” Eason said. “That is the reason we implemented the SmarterMeasure Assessment.”

Students who have never taken an Internet course or who have taken one but did not make a grade better than a C must take the assessment prior to enrolling in a distance learning course.

But beyond basic academic competencies, more intangible traits inform strongly on a student’s likelihood for distance learning success. Without internal motivation, organizational skills and a commitment to study, even the most technologically capable student could still struggle, Eason said.

“Those who study daily, monitor the calendar often and log into the class and check email will be more successful in the class,” he said. “Students who are not disciplined and those who do not log into the class on a regular basis often miss important messages, quizzes, etc., and just one missed grade can bring a good average down.”

And missing assignments means something different to distance learning students. When TCC rolled out its mandatory attendance policy in the spring, on-campus students who fail to attend at least a cumulative 85 percent of the class meetings and do not keep up with assignments can be dropped involuntarily from a class.

In Blackboard, the mandatory attendance policy puts emphasis on students’ completion of a course orientation and active participation in the course as defined by the instructor.

But more than simply completing assignments, differences exist in the academic rigor and depth of instruction achieved in a distance learning environment compared to what is achieved in a traditional classroom setting.

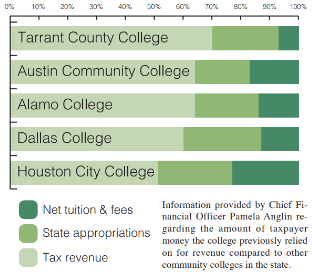

Eason reported that data from fall 2010 showed on-campus students of a given course had a passing percentage of 71 percent while students taking the same class online had a 68 percent passing percentage. Interestingly, Eason reported a lower fail rate for online students, with 13 percent of online students failing the courses compared to 15 percent of students failing the on-campus sections of those same courses.

Coniglio noted this peculiarity in his anecdotal experience with distance learning students when comparing greater academic success or a deeper understanding of chemistry concepts in his lab course by students taking the on-campus versus those taking it online.

“Possibly because [distance learning students] have to spend more time studying the material on their own and have the discipline to work until they understand the material, I often see them do better than students who take the lecture on campus,” he said.

But even the most disciplined distance students will need guidance from their instructor at some point. Distance learning students usually seek instructor guidance via email. While some concepts are difficult to explain, the freedom to ask questions at the precise moment a distance learning student needs help amounts to greater student control over the entire learning process, Eason said.

TCC distance learning faculty are required to check and respond to email five days per week. Eason said email is a critical component of distance learning.

When asked if, in his experience, distance learning faculty regularly honored this commitment, Scripter replied, “the answer is an emphatic NO.”

This can be particularly frustrating for students who are waiting to speak with an instructor before turning in an assignment or taking an exam.

“Immediate response to questions is another big gap [between online and live instruction],” Scripter said. “Questioning a professor directly on a lecture or a grade received is just not there.”

Scripter recalled an recent event that left him ambivalent about distance learning.

After several frustrated attempts to submit a term paper, Scripter sent his instructor an email explaining the problem and sent the paper as an attachment.

Though he sent the email five days before the assignment was due, he didn’t receive a response from the instructor until after the due date had lapsed.

The automatic grading function in Blackboard recorded Scripter’s grade as a zero since he did not submit it through the system. He attempted to call his instructor twice during her posted office hours, but he got her voicemail both times.

Ultimately, the problem was resolved, and Scripter’s grade did not suffer because of the “glitch.” But getting a clear response from the instructor required Scripter to seek departmental intervention.

Eason said the lack of face-to-face interaction is a concern frequently voiced not only by students but by faculty, as well.

Coniglio, who teaches chemistry lecture and lab exclusively via live instruction, said he would be willing to teach a class delivered through distance learning but admitted he had some concerns about the lack of interaction.

“I like really getting to know the students by walking around the lab and talking with them — that [interaction] is a big part of teaching,” he said.

Eason said some distance learning faculty members provide on-campus review sessions or organize other events to encourage in-person interaction. And emerging technologies like discussion boards and video conferencing seek to quickly close the connection gap.

“Some DL classes rely heavily on the discussion boards as graded assignments and being able to go back and review the threads made me feel more connected,” Scripter said.

Eason said students can expect to see faculty employing more numerous and innovative ways of bridging the problems posed by physical distance.

“We know that research shows that the more a student is engaged in the class, with the teacher, with other students, with the material, the more successful they will be,” he said.